There’s More Than One Way In: Becoming a Research Associate

When you’re young and people ask you what you want to be, no one says, “a Research Associate.” I didn’t either. Even as a professional with this title, many of my friends, family members, and peers remain confused about what exactly my job entails. What I did know then, and still carry with me, is that I want my work to matter. I’ve always been curious about the why behind how our world works, and I’ve had a desire to unpack those systems and find ways to make them better, fairer.

In my experience, the underlying connection between those who go into research, regardless of the field, is a deep curiosity, whether about broad societal issues or field-specific dilemmas. Research Associates are problem solvers: we ask hard questions and uncover insights that inform policies and practices, fueling change.

But how do we get to that point? There is no predefined pathway to this work. Unlike careers that have more linear entry tracks, people arrive at research from a wide range of fields—education, social sciences, business, health, technology, hospitality, and more. Each one bringing valuable skills to their work.

Below are just a few ways people, including myself, find their way into research.

Pathway 1: Academia

For many, research begins in school. Many Research Associates hold bachelor’s or master’s degrees related to their focus areas. Academic programs in fields like psychology, business, policy, or education may be foundational for pursuing social science research. They can also open up opportunities to work in labs and support faculty projects.

My first “true research role” came about almost by accident. As a college freshman, I stumbled upon a role that would change my career trajectory: an assistantship in my university’s psychology department, working in the child and adolescent research lab. There, I learned how to collect data, work with research participants, and analyze findings. But most importantly, I learned that research isn’t abstract: it’s about real people and their experiences.

That assistantship gave my curiosity a home, one that was deeply connected to improving lives. It also opened up further opportunities, as I continued with my assistantship once classes resumed, ultimately seeing the study through to completion. Such assistantships can be valuable skill-building opportunities that expand into more substantial roles, but most importantly, they are a time to further develop confidence as a researcher and to find subject areas that you are passionate about.

Pathway 2: Industry

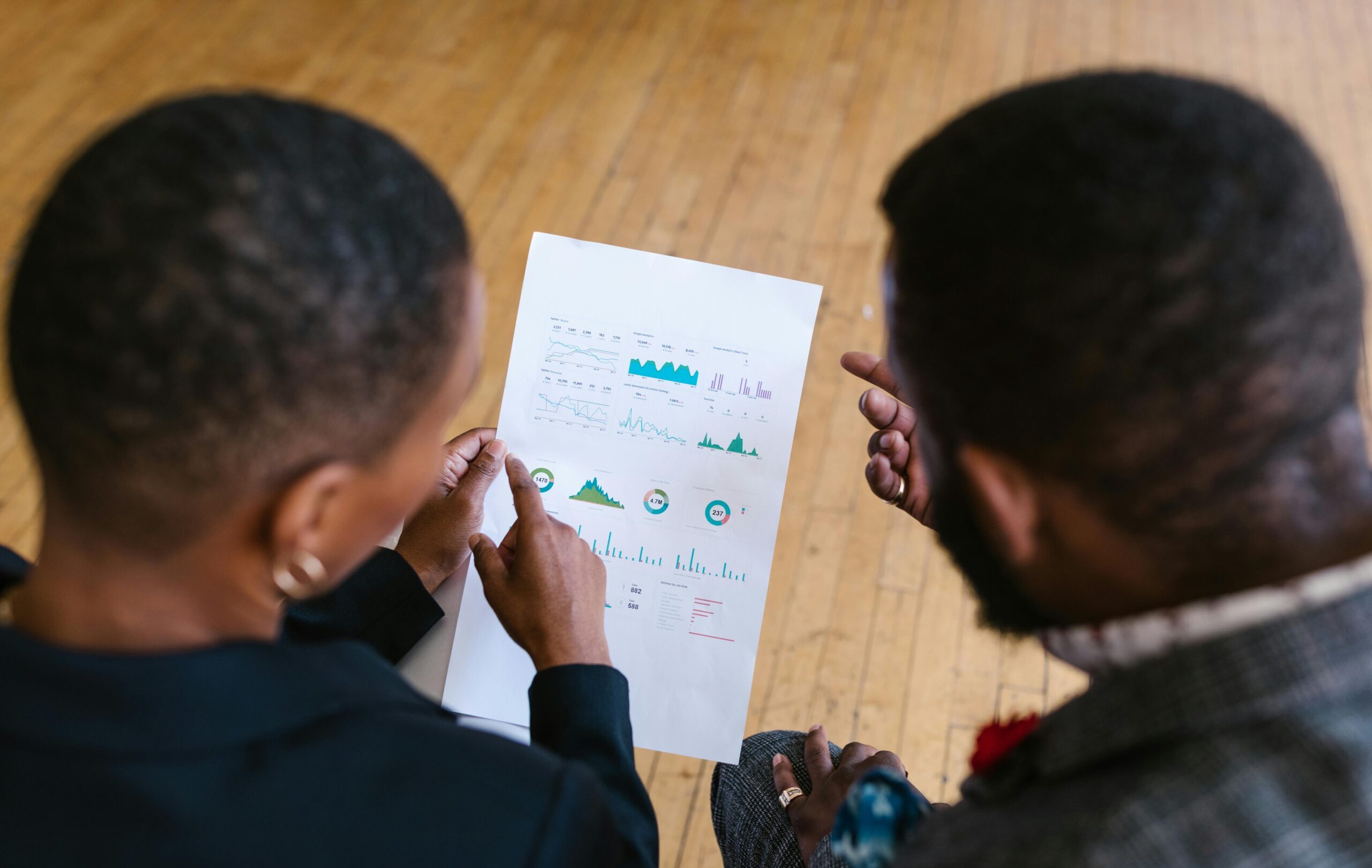

Not all research starts in a lab. I introduce research assistantship as my first “true research role” because I came to it with experience gained from non-research positions. Corporations, non-profits, and other organizations often undertake research and assessment to support their decision-making: collecting data, analyzing trends, and creating reports. Many professionals who begin their careers in roles like project management, marketing, or human resources often discover they’ve developed highly transferable research skills along the way.

My first internship was in project management. It wasn’t a research role by any means, but much of my work focused on site assessments, which gave me my first taste of collecting data to inform change. That experience allowed me to sharpen key skills for research—from more technical abilities such as summarizing and presenting data insights to those of observation, organization, and communication—all skills that I still rely on today as a researcher.

Pathway 3: Roles Outside of Research and Industry

Both “true research roles” and industry pathways can sound like intimidating starting points, but hopefully, I can calm such worries by noting that most of the jobs available to me early in my career were not glamorous.

When I first entered the job market, most of the opportunities available to me were part-time positions: dishwasher, tutor, student orientation leader, residence life manager—sometimes all at once, other times with pauses in between. At the time, these roles didn’t feel like the pathway to a research career, but they were nonetheless important to me in becoming a researcher. These roles helped me build communication and time management skills, often requiring balancing multiple tasks and teamwork under pressure. Such skills are valuable for conducting research that requires facilitating interviews and focus groups, as well as for making sure that the research tasks stay on track.

When I first began my foray into actual research roles, my hospitality experience from working in food service and at an off-campus retreat site was unexpectedly valued for the interpersonal skills that it promoted. It is my perspective that these experiences shouldn’t be dismissed: every role has something to teach you.

Pathway 4: Other Experiential Learning

Even with experience, applying research skills in the real world can feel daunting. Experiential learning and other applications of research skills can further bolster your confidence. For me, volunteering and other small projects became that bridge. For example, I collected and visualized data for student groups, supported local nonprofits with analysis, and lent my skills wherever I could. Each experience reaffirmed my commitment to problem-solving and doing good, while helping me to hone my technical skills.

Through sharing some of my experiences, I hope to show that there is no right way to become a Research Associate—rather, that there are many meaningful paths taken by those pursuing this career. If you are curious and ready to solve a problem, there is likely a research pathway out there that fits you, too.

As a macro social worker, I’ve now come to focus on the so-called “wicked problems”. Wicked problems are social policy dilemmas that are pervasive, complex, not clearly defined, and notably lack a singular, clear solution. At EduDream, as our team works with nonprofits, foundations, and education institutions to provide culturally responsive and community-centered research and strategy, we encounter many of the intersecting social issues that make the U.S. education system a classic example of a wicked problem. From limited resource access, assessment and accountability, socioeconomic and racial inequities, and issues of teacher quality and compensation. These problems are intertwined, and there is no singular solution that fits them all. From my perspective, that makes education all the more meaningful to work on improving.

Interested in learning about early career research opportunities with EduDream?

At EduDream, we’re passionate about supporting researchers from all backgrounds, especially those who bring unique experiences and a desire to tackle challenging problems within the education system. If you’re curious about internships, research assistantships, or other opportunities for early career roles, we’d love to hear from you. Share your resume and interest at info@edudream.org.