Debunking Debt: The Drive for Student Loan Forgiveness

Last month, in derailing President Biden’s plan to relieve $400 billion in student debt, the Supreme Court delivered a setback to our country’s ideals of education for all. College affordability and the student loan crisis are equity issues with deep-seated ramifications for current and future Americans.

Journalist Josh Mitchell, author of The Debt Trap: How Student Loans Became a National Catastrophe, details how the student loan industry emerged in the 1950s to increase the number of college-educated Americans who could later work in national security roles. Given the Cold War and subsequently the Vietnam War contexts, loaning to individual borrowers was a palatable solution to the federal government at a time when socialist-adjacent free education was undesirable, and increasing the federal deficit by paying for college-goers’ tuition appeared untenable. In 1958, Congress passed The National Defense Education Act, creating the first federal loan program, though it was not until 1972 that the corporation later renamed Sallie Mae was created out of the HEA Reauthorization Act. Congress originally created Sallie Mae as a “government-sponsored enterprise,” allowing it to use federal monies to purchase loans from banks, and borrow money at extremely low rates. Since 1980, and accelerating after its privatization in 2004, the company was allowed to freely issue student loans with little consideration of individuals’ likely ability to pay it back.

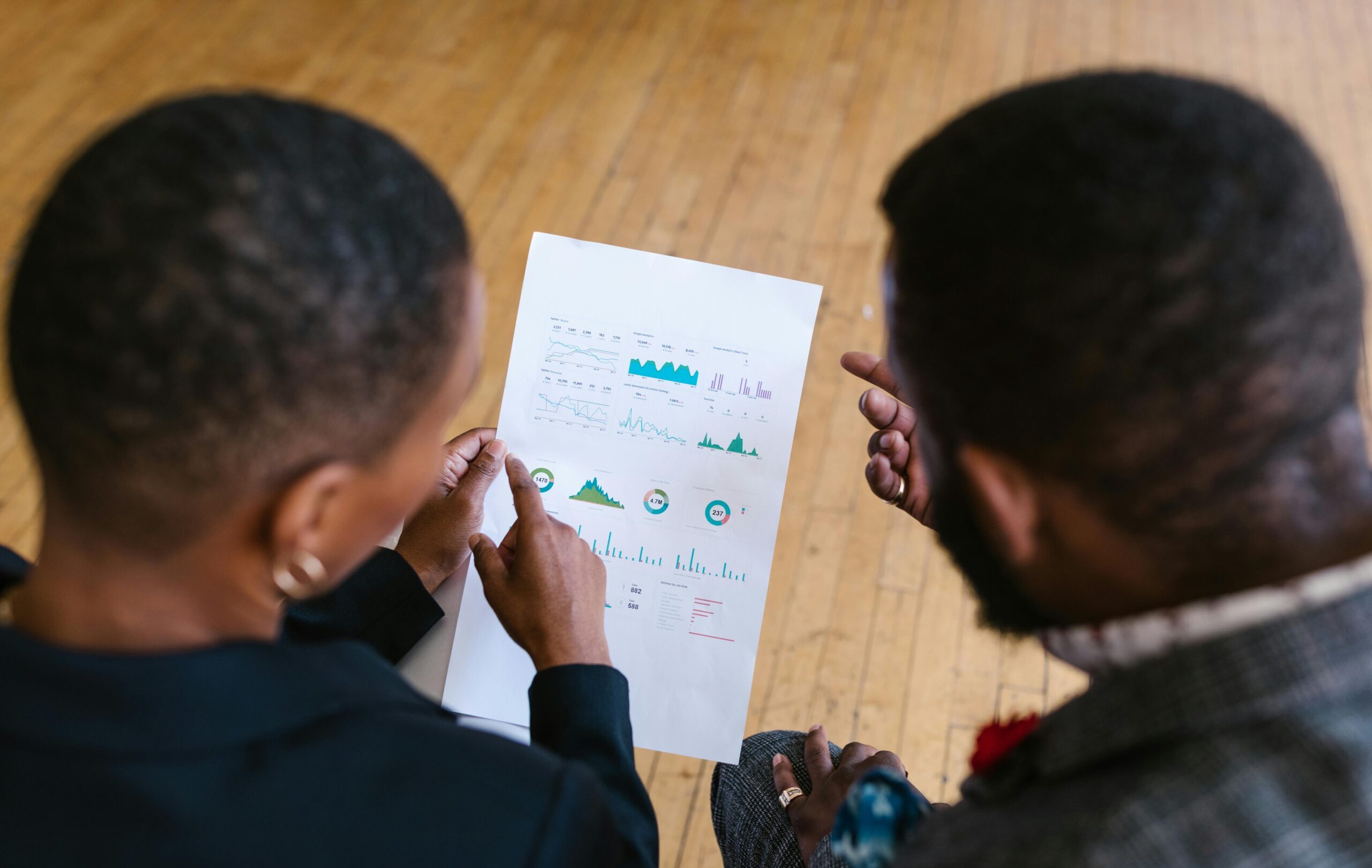

Flash forward to today, six decades and multiple policy changes later, the scale of the student debt crisis is stark. Average inflation-adjusted college tuition and fee rates have increased 130% since 1990. It is no wonder why more and more borrowers have had to turn to loans to finance higher education, in part due to the ever-expanding credential requirements, known as degree inflation. Today, 1 in 6 American adults have some student loan debt, totaling more than $1.7 trillion, and more than 90% of that debt is from federal student loans.

For decades, a college degree was pushed as the premier mechanism of social mobility: earn a degree, secure a well-paying job, and create more stability for oneself and future generations. While there is some truth to this, wage depreciation and the rising costs of housing, childcare, and, more recently, groceries have meant that for many borrowers, no matter how hard they work or how little they spend, student loans (and interest) have become overly burdensome and nearly impossible to pay off, as these testimonials from the NAACP convey.

Much like the housing crisis in 2008, student loans were given out by financial institutions seeking to make enormous profits with little regard to borrowers’ abilities to repay. But when the housing crisis boiled over, the government averted an even greater financial meltdown via payouts of $498 billion to bail out various financial institutions. This was seen as a necessary action to prevent further global economic crisis. We need to make a similar investment – this time, removing crushing debt for millions of American families, some of whom were defrauded by colleges with respect to their job prospects or their likely salary after graduation, and acknowledging the predatory nature of the student loan industry. This is especially true for Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian American borrowers who have been historically excluded from the creation of generational wealth. Relieving the student debt crisis is just one piece of this investment: one that makes a bold statement proclaiming student loan relief as an equity lever, and holding an oppressive industry accountable.

America is a highly individualistic country, yet humans are inherently communal. Student debt forgiveness does not negate personal agency; rather, it provides opportunities for more than 43 million borrowers to spend or invest that money into their communities. Young people are delaying home ownership, starting families, or saving for retirement because of this debt that has not delivered on its promise of financial security. Is putting on hold decades of lives what we, as a society, value? For what benefit? We must look at the benefits of higher education together with the consequences of rampant student loans and the rising costs of college, and ask ourselves: what do we value?

If we value home ownership and education as both personal and communal investments that should be accessible to as many Americans as possible, and in a manner that is racially equitable, then we must chart a path forward. A path that reflects our American values and requires elected officials to keep pushing on this issue, and remain fueled rather than deterred by the Supreme Court setback. The new SAVE Repayment Plan will lower the repayment amount for enrolled individuals and protect against balances growing from unpaid interest. Additionally, the Department of Education is set to provide a one-year on-ramp to repayment and begin discharging loans for over 800,000 individuals who have made the necessary number of payments under income-driven repayment plans. The administration has taken the first step to pursue negotiated rulemaking, a complex, often lengthy, public policy process, as a way to continue fighting for loan forgiveness. But even more aggressive, and timely, action is needed.